History

Early History of Pensacola

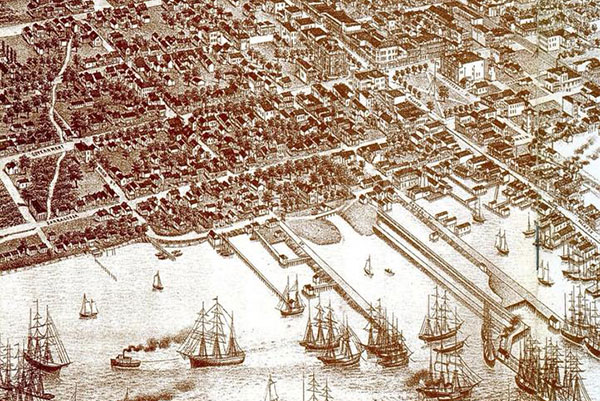

First settled by Spaniards in 1559, Pensacola is the oldest European settlement in mainland America. The location - south of the original British colonies and near the dividing line between French Louisiana and Spanish Florida - has caused Pensacola to change ownership several times. Pensacola was Spanish, then French, then Spanish, then British, then Spanish again, before becoming American, then Confederate, and then the current U.S. city.

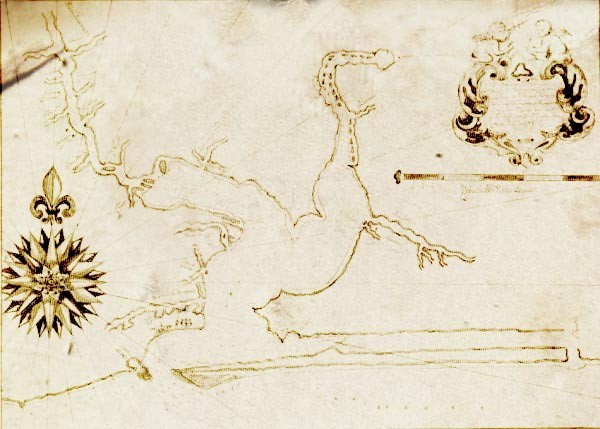

Early exploration of Pensacola Bay (called Polonza or Ochuse) spanned decades, with the likes of Ponce de León (1513), Pánfilo de Narváez (1528), and Hernando de Soto (1539) charting the area. Due to prior exploration, the first settlement of Pensacola was large, landing on August 15, 1559, and led by Don Tristán de Luna y Arellano with over 1,400 people on 11 ships from Vera Cruz, Mexico. However, weeks later, the colony was decimated by a hurricane on September 19, 1559, which killed hundreds, sank 5 ships, grounded another, and ruined supplies. The 1,000 survivors divided to relocate and resupply the settlement, but due to famine and attacks, the effort was abandoned in 1561. About 240 people sailed to Santa Elena (today's Parris Island, South Carolina), but another storm hit there, so they sailed to Cuba and scattered. The remaining 50 at Pensacola were taken back to Mexico, and the Viceroy's advisors concluded northwest Florida was too dangerous to settle. Efforts to do so ceased for another 135 years.

Spanish Influence

The banners of five nations, Spain, France, England, the Confederate States of America, and the United States, have flown over the city of Pensacola, giving rise to its nickname, The City of Five Flags. Pensacola is Florida’s second oldest city and has the deepest bay on the Gulf Coast. The mouth of the bay is bounded by Santa Rosa Island to the east and Perdido Key to the west. To guard the entrance, Spain established Fort Barrancas atop a 60-foot bluff on the mainland opposite the bay’s mouth. Soon after the United States took control of Florida from Spain in 1821, the federal government, recognizing the importance of Pensacola’s harbor, moved to establish both a naval yard and lighthouse there.

The First Lighthouse

In March of 1823, Congress authorized $6,000 for the Pensacola Lighthouse. To serve the port until the lighthouse was finished, the floating light vessel Aurora Borealis was transferred from the mouth of the Mississippi, where the Frank’s Island Lighthouse had just been completed. The vessel was positioned in calm waters behind the western end of Santa Rosa Island. A site just west of Fort Barrancas was selected for the lighthouse. Ships would be able to steer directly towards the light to enter the harbor, something that was not possible with the lightship.

On March 24, 1824, Winslow Lewis, responding to an advertisement in the Boston Patriot, offered to build the lighthouse and dwelling for $4,927. For an additional cost of $750, Lewis would “fit up and Light the Light House with ten patent Lamps and ten fourteen inch Reflectors and furnish two spare Lamps, six double tin oil butts to hold ninety gallons each, six wooden boxes, One lantern canister, and trivet. One tube box. One wick box. One oil carrier. One torch. One hand lantern Lamp. One oil feeder. Two files. Two pairs of scissors. Six wick formers and have it completed in thirty days after the Light House is finished.” Lewis’ offer was accepted by Stephen Pleasonton, fifth auditor of the Treasury, on April 2, 1824.

The new tower was first lit on December 20, 1824, by bachelor Jeremiah Ingraham. To produce a flashing signature, two groups of five lamps were fastened to opposite ends of a framework, which was rotated by a clockwork system. After two years at the post, Ingraham married Michaela Penalber of Pensacola. Together, they managed the light and raised three children at the station. When Jeremiah passed away in 1840, Michaela took over responsibility for the light. In the late 1840s, the clockwork mechanism failed and two men were hired to rotate the lamps by hand until repairs were made. Michaela served until her own death in 1855, when her son-in-law, Joseph Palmes, was hired as the keeper.

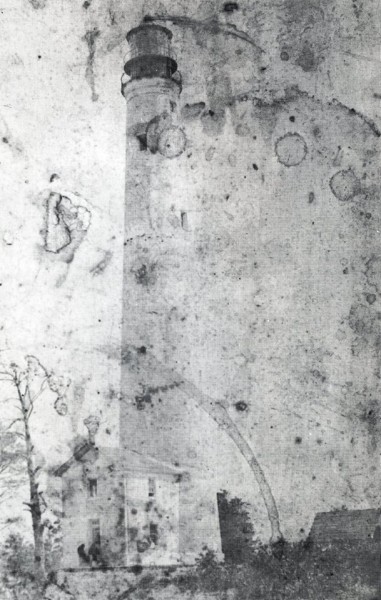

By 1850, regular complaints were starting to be voiced regarding the lighthouse. Trees on Santa Rosa Island were said to block the light, and the light was considered too dim. In 1852, the newly established Lighthouse Board recommended that a “first-class seacoast light” with a height no less than 150 feet be built at Pensacola. Congress allocated $25,000 for the lighthouse in 1854, and an additional $30,000 in 1856. A site was selected one-half mile west of the original lighthouse, and work on the tower was supervised by John Newton of the Army Corps of Engineers. The construction was completed in 1858, and the lamp in the tower’s first-order Fresnel lens was first lit on New Year’s Day, 1859 by Keeper Palmes. The tower stood 159-feet-tall and was painted white. The base of the tower had a diameter of 30 feet, tapering to a diameter of 15 feet at the top.

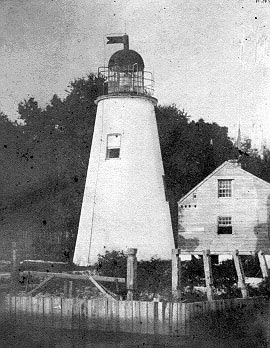

Unfortunately, there are no existing photos of the first Pensacola Lighthouse. Pictured above is the Tchefuncte River Lighthouse, which was contemporary to the first Pensacola Lighthouse and was also outfitted by Winslow Lewis. It is likely that our 1824 lighthouse looked very similar to this one.

The Civil War

On January 10, 1861, Florida seceded from the United States. Union forces abandoned Fort Barrancas in favor of Fort Pickens, on the western end of Santa Rosa Island. The Confederates took control of the tower, and eventually discontinued the light and removed the lens. The opposing forces warily watched one another across the bay for months. Then on November 22, 1861, a two-day artillery battle erupted. The “Lighthouse Batteries” were frequent targets for the guns of Fort Pickens, and roughly half a dozen rounds struck the tower. Confederates evacuated the area on May 9, 1862, and the lighthouse fell under Union control. None of the rounds penetrated the outer wall of the lighthouse, and the tower was found to be in good condition. A fourth-order lens was placed in the lantern room, and the tower was lit again on December 20, 1862.

The original first-order Fresnel lens was recovered after the war and was re-installed in the tower’s lantern room in 1869. That same year, a new dwelling was built for the keepers, and the tower’s day mark was changed. The bottom third of the tower remained white to stand out against the trees, but the top portion was painted black to stand out against a possibly cloud-filled sky

Natural Disasters

Who says lightning doesn’t strike twice in the same place? The Pensacola Lighthouse was zapped in 1874 and then struck again the following year. The tower’s lightning rod was shown to be defective, as the surge of electricity melted metal fixtures in the lighthouse. Nature took another swipe at the lighthouse on August 31, 1886, when a rare earthquake shook the tower. A keeper penned the following report on the earthquake: “It lasted between three and four minutes, and was accompanied by a rumbling as if people were ascending the steps making as much noise as possible. This shock was like a tremor, causing the lens to vibrate from side to side. The pendulum clock on the lower floor was stopped by the shock at 9:07 p.m.” In the period between the lightning strikes and the earthquake, cracks were discovered in the tower. It was thought that they might have been caused by the shot the tower received during the Civil War coupled with the strain from subsequent hurricanes. The Lighthouse Board acted quickly to re-point the tower from top to bottom

Pensacola Lighthouse: A Timeline